Methodologically, reflecting on the contemporary also allows us to reexamine some of the ways in which industry as such has been

conceptualized or imagined not only through media scholarship but by the “industries”

themselves. Some contemporary “industry scholars” have begun calling, what our

readings have described, the “industry” as an “ecology” or media ecology, in

order to think about the dynamism and vibrancy of industrial formations and

configurations. (Zahlten 2017, Lamarre 2018). Although I currently don’t have

any really developed thoughts or critical positions towards contributing

towards scholarship about media industries/ecologies, thinking about the

contemporary highlights some of the analytical and conceptual limits of more "traditional" approaches to industry studies. At the same time, focusing on the

contemporary industries and approaches to industries allows us to trace the

ways in which they developed historically and discursively. Holt sharply

emphasizes the role of media industries at the time of her writing, citing

Peter Bart: “a major player ‘must mobilize a vast array of global brands to

command both content and distribution. Indeed, such an enterprise must be more

than a company – it must be a virtual nation state.’” (Holt 11)

Certainly, that seems to be the case with Japan’s animation

industry, in which one might conflate the industry to Japan’s national identity

itself. There was recent controversy around the very popular series, My Hero

Academia, where a character’s name drew immense criticism from China and

South Korea. The controversy led to Chinese

platforms Tencent and Bilibili removing both comic and animation from their

libraries. This comes a couple of years after successful theatrical runs of Spirited

Away (officially screened a decade past its initial release) and Your

Name. Simply put, not only are these “enterprises” perceived as a

virtual nation state, but they must “behave” as if they were a virtual nation

state as well.

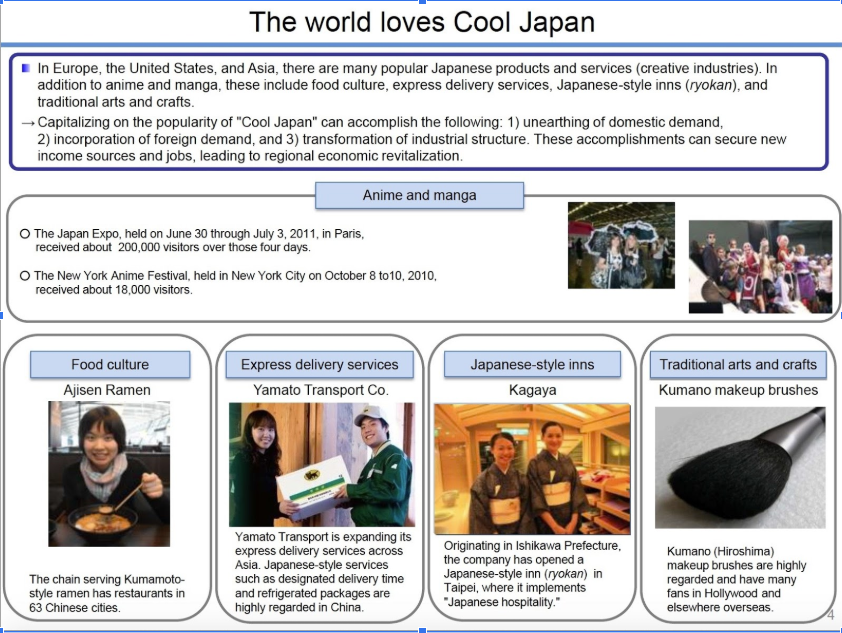

Enter Japan’s METI’s Cool Japan project. The project initially

sought to meet the “global demand” of product that wasn’t as demanded domestically.

The following image is taken from the initial 2012 draft of the Cool Japan

project, tentatively titled Cool Japan Strategy:

Figure 1 (Cool Japan Strategy January 2012 draft)

Whereas Cool Japan might have initially described medium

specific things of Japan’s popular culture in the 90s and early 00’s (Allison 2006),

this 2012 draft sought expanding Cool Japan into including more “aspects” of

Japanese culture in order to develop creative industries elsewhere.

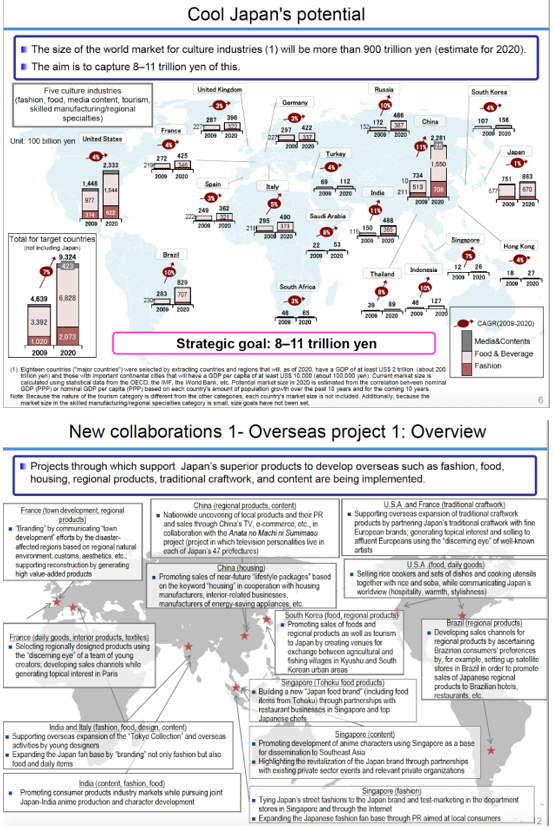

The following images from the same draft uses cartographic renderings

of the “world” in which METI conceptualizes that world in terms of potential

market points for the project and various creative industries:

Figure 2 (Top and bottom images are both from Cool Japan Strategy

January 2012 draft)

I want to emphasize that the latter image presumes that the products/creative

industries imagined within this global market are both desirable and assimilable.

But more importantly, various combinations of products and industries are

imagined in different markets: India and Italy are conceptualized as potential

markets for fashion, food, design, and content, South Korea is food and

regional product, France is listed with “town development” and “daily goods”,

etc. There are many possible reasons for the different combinations of products

and industries imagined for each market, such as: the market might already have

a robust industry of that particular stuff, the market’s familiarity with Japanese

product or culture is with this stuff and not that stuff, or certain political

or economic relations allow for, or resist, certain things.

However, the “Cool Japan” strategy/policy/phenomenon is not

the “first of its kind.” There have been other policies that sought similar

efforts, such as Cool Britannia and the Cool Korea Strategy in 1997. And this

brings me to some questions: what is the work of “Cool” and why target cultural

product and creative industries?

Holt and Caldwell’s essays certainly provide models of

analysis towards answering these questions. For Holt, policies are the discursive,

material, and literal realizations of the relationships between industries and

governments. I feel the same. Analyzing policies become a way to unpack how these relationships

are configured and imagined. Yet this approach seems to gloss over the

specificity of the products that do circulate—the stuff that sells—and why they

circulate. Simply put, markets need to buy into the product you’re selling, it

needs to appeal to them in whatever localized, regionalized, globalized way

that allows those industries to “expand” and do their work. Recent studies show

that Cool

Japan is “failing”. The global market isn’t buying what Japan’s METI is

selling, but that doesn’t mean that it’s not buying what the Japanese animation

industry is producing. The recent 2019 annual report from the Association of

Japanese Animators shows the

sixth straight year of revenue growth earning an industry-wide 2.1814 trillion

yen, or 10.939 billion dollars. Why the gap? Where can we locate the gap? What

is the gap?

Caldwell’s work on the stunt-genre and critical industrial

design, for me, provides one way into exploring this gap. If METI thought that Cool Japan was “this”,

and has been enacted as “this”, but failing at “this”, while thinking all this

time that "this" was “that,” then what are the differences between “this” and “that”? Is the Japanese animation industry, or some studios, doing "that"? Maybe it's something different from what Cool Japan meant initially during the 80s/90/s/early 00s. I personally feel that this question and related questions require similarly different answers that deploy the historical, textual, and conceptual approaches of all three readings for this week.

Historically, the economic stagnation of 2009 might have

encouraged Japan’s METI to enact the policy 3 years after the global financial

crisis, hoping that the “expansion” into the global market (again?) might bear

the same fruit of some international economic success during Japan’s Lost

Decade. The rising anti-Japanese rhetoric emerging into the global conversation

from Japan’s imperial history from countries like China, South Korea, and

Taiwan might have also forced Japan’s government to deploy “Cool Japan” as a

means to deflect “Imperial Japan.” (Ching 2019)

Aesthetically, the appeal of Japanese animation continues to

growth globally, or at the very least, the commercial appeal of it. Where is the

appeal coming from? Koichi Iwabuchi suggests that it’s the lack of “cultural odor”, 無国籍 , or "Japanese-ness" 日本人論 that allows for a globalized

legibility for the non-Japanese market. (Iwabuchi 2002) Yet such assimilability

seems to be conditional on past and present political and economic relations, such

as the My Hero Academia controversy. So how can one locate, examine, or

analyze that appeal which continues to commercially grow? For myself, one way

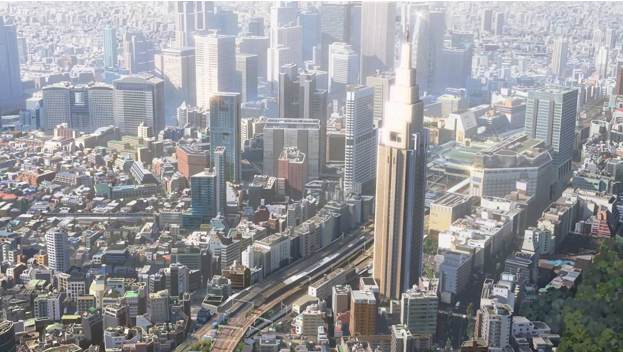

into grappling with that appeal is through looking at representations of environment

and space in isekai anime. Isekai (different world) is a fantasy subgenre

of Japanese light novels, comic, anime, and video games that generally revolve

around the protagonist transporting from Earth to another parallel universe.

These parallel universes are typically depicted as a fantasy world, laden with

iconographies of vast fantastical landscapes, characters, and object. How might

these spatial aesthetics narrativize or characterize not just isekai anime

or anime as such, but Japan’s animation industry as textually and commercially

appealing to the non-Japanese market? What are the similarities and differences

between representations of environments and spaces in isekai and other “genres”?

Under what conditions does that appeal fail?

Figure 3 (“Tokyo” in Your Name)

Figure 4 (Fantasy world in KonoSuba: God's Blessing on

this Wonderful World!)

Figure 5 (Fantasy world in Log Horizon)

Conceptually, I continue to grapple with “industry.” I

entered the CAMS program as an “industry scholar” but had no idea what that

entailed in terms of “industry” as an object of analysis. I was faced with a

lot of epistemological questions. At the end of the MA, I am confronted with

a similar set of intellectual questions pertaining to approaches to, and

definitions of, “industry.” It might be the division of labor, corporate strategy,

annual sales reports, cultural policy, regulation, critical industrial design,

or dynamic producer-consumer relationships. Ideally, I’d like to pitch a model

that can address them all, yet I know that no one’s going to buy that.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts on the "Cool Japan." Your analysis of "Cool Japan" strategy and phenomenon with self-reflexive contemplation on the methodologies of industry studies is very insightful, especially in terms of thinking about the complex global flow that national/regional cultural policy has created. This is just a random thought, but I cannot help but think about some of the critical comments on the "Cool Japan" strategy made by Japanese artists, including Takashi Murakami and how these commentaries have formed an ecology surrounding Cool Japan. Murakami himself is very successful in achieving a wider circulation of his works and is highly conscious of the potentiality of the global market; however, Murakami is very critical on Cool Japan by saying he has nothing to do with it. He proposes a unique concept called "superflat" to analyze some sensibilities shared in the cultural production in Japan. Looking at comments by various artists and practitioners who have pitted themselves against the Cool Japan policy, I wonder how we can understand the complex ecology surrounding this government project and its wider discursive quality.

ReplyDeleteSorry my name does not appear... The comment above is from Wakae Nakane.

ReplyDelete